Islands of Control, Islands of Resistance: Monitoring the 2013 Indonesian IGF

Download the full report here.

Read the individual sections here:

- IGF 2013: Islands of Control, Islands of Resistance: Monitoring the 2013 Indonesian IGF (Foreword)

- IGF 2013: Monitoring Information Controls During the Bali IGF (Framing Post)

- IGF 2013: An Overview of Indonesian Internet Infrastructure and Governance (Part 1 of 4)

- IGF 2013: Analyzing Content Controls in Indonesia (Part 2 of 4)

- IGF 2013: Exploring Communications Surveillance in Indonesia (Part 3 of 4)

- IGF 2013: An Analysis of the 2013 IGF and the Future of Internet Governance in Indonesia (Part 4 of 4)

As our framing post outlined, surveillance is one of the most effective, if less obvious, forms of information control. Governments and private companies engage in surveillance for a wide range of reasons, many of them beneficial for society. However, surveillance can also be used to target dissidents and undermine privacy. If surveillance is undertaken without proper accountability, it can lead to the abuse of power. Surveillance of the Internet and other communications is now a huge growth industry, with many companies supplying governments with passive and targeted surveillance products and services.

Citizen Lab research has documented the use of surveillance technologies, products, and services in Indonesia, including those designed for or capable of targeted (FinFisher) and passive (Blue Coat) surveillance. Additionally, smartphone maker BlackBerry (previously known as Research in Motion) has come under pressure from Indonesian authorities to locate back-end infrastructure within the country as a means of facilitating surveillance of users. BlackBerry, as well as other electronic service providers, has continued to be pressed by the Indonesian government to locate their data centres in Indonesia, in line with the government regulation 82 of 2012 on the Operation of Electronic Systems and Transactions.

This post summarizes Citizen Lab’s prior research on surveillance in Indonesia, including documented evidence of FinFisher command-and-control servers and Blue Coat Systems devices on IPs owned by Indonesian ISPs. It also identifies recent trends in Indonesian surveillance practices, laws, and regulations that provide potential avenues for further research.

Prior Research: Censorship and Surveillance in Indonesia

FinFisher

Citizen Lab research has documented the use of surveillance technologies, products, and services in Indonesia. Since 2012, Citizen Lab researchers have revealed the presence of FinFisher command-and-control (C2) servers in thirty-six countries across the globe, including Indonesia. These findings have led to activists and advocacy groups in several countries launching legal complaints in national and international settings, including in Pakistan, Mexico, the United Kingdom, and the OECD. We have translated a “fact sheet” about our findings from English to Malay and Indonesian.

FinFisher is a commercial surveillance toolkit that provides an attacker with remote control and access over a target’s computer system. According to leaked promotional materials, FinSpy, a component of the FinFisher suite, is capable of exfiltrating data; intercepting e-mail, instant messaging, and VoIP communications; and spying on users through webcams and microphones. Captured information is then transmitted to a designated FinSpy C2 server. FinFisher is developed by Munich-based Gamma International GmbH. The UK-based Gamma Group advertises FinFisher as a suite of “governmental IT intrusion and remote monitoring solutions” and claims to sell exclusively to law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

In August 2012, Citizen Lab published The Smartphone Who Loved Me, in which researchers identified potential FinSpy C2 servers in ten countries by scanning IP addresses and fingerprinting for FinSpy’s characteristic C2 protocol. Among the observed servers was an IP (112.78.143.26) owned by Biznet, an Indonesian ISP. Martin Muench, the managing director of Gamma Group, publicly denied that the scanned servers were connected to any component of the FinFisher suite.

In a March 2013 follow-up report titled You Only Click Twice, Citizen Lab identified thirty-six FinSpy servers (thirty new, six previously identified) in nineteen different countries, many of which have a history of human rights violations. The report documented four additional C2 servers in Indonesia on three IPs belonging to ISPs Biznet (112.78.143.34), PT Matrixnet Global (103.38.xxx.xxx), and PT Telkom (118.97.xxx.xxx). During the course of this research, we found mobile-related evidence with a specific connection to Indonesia that is significant and deserves further scrutiny. The FinFisher product for mobile phones can send stolen data back using SMS messages. We found one sample of a mobile phone version of FinFisher that contained a phone number in Indonesia, which the spyware used to send stolen data back over SMS.

Our researchers did not know who was targeted with this particular sample, but infer that the people who were targeted were likely in Indonesia because the SMS number was there. Usually there is a charge for sending international text messages, which is levied by the telecom company that a user subscribes to. If charges for sending international text messages begin to appear on a phone bill, and the target knows they did not send those messages, they may become suspicious. Our researchers inferred from this reasoning that the use of an Indonesian phone number indicates that there are people in Indonesia who are targeted with FinFisher. The phone number we identified in the FinFisher sample was:

Although these findings have raised alarms among activists and media, it’s important to be clear about several contextual points. The presence of FinFisher C2 server in a particular country is not necessarily proof that the government is responsible for purchasing or operating the FinFisher suite. Someone could be operating the C2 server from another jurisdiction, and using the location to mask attribution. Moreover, there are legitimate ends to which law enforcement and other government agencies might employ the FinFisher toolkit, such as legally “wiretapping” suspected criminals (i.e., with a judicial warrant). However, products used by law enforcement and government agencies for “lawful interception” become problematic in countries with weak rule of law and where dissident activities are viewed as criminal, or where military and intelligence agencies have a track record of targeting local populations or civil society. For example, the Citizen Lab has found evidence of FinFisher being used to target Bahraini activists as well as evidence of FinFisher campaigns with political content relevant to Ethiopia and Malaysia.

In response to Citizen Lab’s findings, a spokesperson for Indonesia’s Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (MCIT) stated that the ministry would evaluate the information and take “decisive action” if Biznet, PT Telkom, and other ISPs were operating surveillance software. The ministry further stated that any such act would constitute a violation of article 40 of Indonesia’s Telecommunications Act, which explicitly prohibits unlawful eavesdropping on information transmitted over telecommunications networks. The implication that the ISPs themselves were responsible for the purchase of FinFisher software contradicts Gamma Group’s claim to sell only to governmental entities.

Blue Coat

Blue Coat Systems is a California-based provider of network security and optimization appliances with functionality permitting network filtering and surveillance. These include: ProxySG devices that work with WebFilter, which categorizes Web pages to permit filtering of unwanted content; PacketShaper, a cloud-based networking management device that can establish visibility of over six hundred web applications and control undesirable traffic; and CacheFlow, a Web-caching appliance that functions to optimize bandwidth. ProxySG provides “SSL Inspection” services to solve “issues with intercepting SSL for your end-users.” PacketShaper has the ability to monitor and control network traffic: it is integrated with WebPulse, Blue Coat Systems’ real-time network intelligence service that can filter application traffic by content category. CacheFlow can be configured to block content. While these Blue Coat products can be used to maintain and secure networks, they can also be used to implement politically motivated restrictions on access to information, and monitor and record private communications.

The Citizen Lab has conducted research on Blue Coat Systems products using a combination of wide-area scanning techniques, Shodan queries, and other experimental methods. Citizen Lab researchers have found Blue Coat devices on the public networks of eighty-three countries (twenty countries with both ProxySG and PacketShaper, fifty-six countries with PacketShaper only, and seven countries with ProxySG only).

In a January 2013 report titled Planet Blue Coat: Mapping Global Censorship and Surveillance Tools, Citizen Lab discovered PacketShaper installations in Indonesia on the networks of both Indosat (http://202.155.63.62/) and PT Telkom (http://203.130.193.156/login.htm). The Citizen Lab also found installations of CacheFlow on PT Telkom (http://180.252.181.1). Citizen Lab researchers connected to the Blue Coat devices to confirm that they were active.

The presence of Blue Coat devices in a country does not necessarily imply that they are being deployed for surveillance. However, their presence raises substantial concerns, particularly in light of Citizen Lab finding FinFisher on three Indonesian ISPs as well as governmental pressure exerted on BlackBerry to locate its back-end servers within the country as a means of facilitating surveillance of users. Additional concerns revolve around the lack of rigorous independent oversight for Indonesia’s State Intelligence Agency (Badan Intelijen Negara, BIN). In light of these findings and this context, further investigation is required.

Blue Coat Systems offers product certification courses through a number of “Authorized Training Centers,” such as Red Education. Headquartered in North Sydney, Australia, Red Education offers courses on information technology and computer networking, and has training centres across the globe including in Jakarta. The company offers training courses in PacketShaper and ProxySG administration, as well as certification exams for Blue Coat proxy administrators and professionals.

Trends in Surveillance and Further Issues for Research

BlackBerry

Indonesia is a significant market for Canadian telecommunications company and smartphone manufacturer BlackBerry Ltd. As of 2013, analysts estimated that approximately 15 million BlackBerry users are in Indonesia, accounting for almost 20 percent of all BlackBerry consumers worldwide.

In a multistakeholder meeting in January 2011, BlackBerry agreed to comply with four demands the Indonesian government stipulated, including the creation of domestic after-sales service centres, the establishment of network aggregators or servers on Indonesian soil, the implementation of government censorship requirements for Internet content, and an agreement to discuss the possibility of granting Indonesian law enforcement “lawful interception access” to key BlackBerry services. BlackBerry implemented the government’s filtering requirements, established forty service centers, and claimed to have fulfilled the “lawful interception” condition (i.e., will provide access to its network if a violation occurs) through coordination with Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission, but the company did not disclose further details about its implementation.

Despite BlackBerry’s claims, the Indonesian Telecommunications Regulatory Body (Badan Regulasi Telekomunikasi Indonesia, BRTI) filed a complaint against the company for locating a key data centre in Singapore rather than Indonesia as requested. The BRTI threatened to shut down BlackBerry Messenger (BBM) and BlackBerry Internet Service (BIS), claiming that the use of servers in Canada to process BBM and BIS data threatened the security of Indonesian users. The Indonesian government has also argued that local servers are necessary for monitoring criminals and terrorists using the BlackBerry platform for communications.

Indonesia’s requirement to locate servers within its borders reflects a trend BlackBerry encountered when it began operating in countries with significant controls over information. Concerns over monitoring citizens’ communications have prompted the governments of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to make similar demands of the company. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates also threatened to ban BlackBerry data and messaging services due to alleged security concerns. As with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, Indonesia is facing the challenge of controlling information on devices whose traffic is processed outside of its jurisdiction. During an open discussion held by the Indonesian E-commerce Association (IdEA) in May 2013 in Jakarta, MCIT’s Director General of Informatics Application, Ashwin Sasongko, said, “If the data centers are located overseas and there are issues, (Indonesian) law enforcement will face problems in getting to the data. Law enforcers cannot gain physical access because it’s in another country.” As of 2013, BlackBerry has not yet built a server inside Indonesia.

Gamma TSE

Indonesia’s military establishment has bolstered its surveillance capabilities through international partnerships and commercial purchases. From 2006 to 2008, the US government provided a USD 57 million outlay to Indonesia for the establishment of an Integrated Maritime Surveillance System (IMSS), designed to combat terrorism, smuggling, and piracy in Indonesian waters. The system includes surveillance cameras, surface radar, global position systems, and other combinations of sensors, devices, and technical platforms to monitor maritime traffic.

The Indonesian military recently purchased “unspecified ‘wiretapping’ equipment” from Gamma TSE. The undisclosed equipment will be used by the TNI’s Strategic Intelligence Agency. Privacy International described this deal as “deeply troubling” given the Gamma Group’s previous commercial deals with authoritarian regimes and the Indonesian military’s history of human rights violations. Members of Indonesia’s House of Representatives also expressed concern that surveillance equipment could be abused in the run-up to the 2014 general election. The House Commission on Defense and Information warned the military not to use any purchased equipment for politically motivated surveillance.

Legal Environment and Surveillance

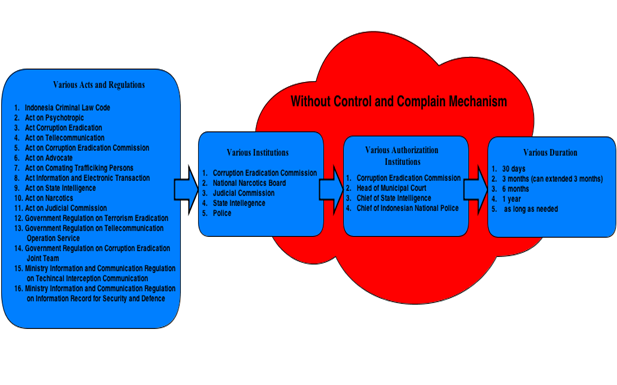

As we mentioned in our Infrastructure and Governance post, there are many laws that regulate interception and wiretapping in Indonesia. Figure 1 shows that at least twelve laws, two government regulations, and two ministerial regulations outline the practice of wiretapping by state institutions in the name of law enforcement. This is because communication interceptions today are usually carried out by law enforcement agencies to expose crimes, particularly organized and transnational crimes. In many of these cases, wiretapping was helpful, even necessary. However, they are also prone to misuse and may lead to violations of privacy without comprehensive legislation regulating their use.

In January 2013, Gatot S. Dewa Broto, the spokesperson for the MCIT, stated that the government as a whole is preparing a draft law on interception mechanisms (RUU Tata Cara Intersepsi).

Figure 1. Various acts and regulations governing interception and wiretapping1

However, prior to the attention the Constitutional Court generated by annulling article 31(4) in the Electronic Information and Transactions Act, the debate about interception was stirred by the enactment of Act No. 17 Year 2011 on State Intelligence, which was widely criticized for granting broader authority, and not enough accountability, to the State Intelligence Agency to intercept communications. The Alliance of Independent Journalists, four nongovernmental organizations, and thirteen individuals subsequently filed a judicial review of the act at the Constitutional Court in Jakarta in January 2012. They were concerned with its vague and broadly defined articles, for instance, on the issue of “intelligence secrets,” and the opportunity that it provides authorities to classify public information as state intelligence. These provisions imperil journalists because using or citing documents that had been classified could be deemed a crime. Certain articles also evoked fears of surveillance by “Big Brother,” such as article 29 which gives the State Intelligence Agency power over foreigners or foreign institutions planning to take Indonesian citizenship, or visit, work, study, or open a representative office in the country. In October 2012, the Constitutional Court turned down the judicial review, arguing that the act “appropriately regulated intelligence practices in Indonesia.”

The State Intelligence Law is one of at least nine laws that allows the authorities to conduct surveillance or wiretapping, and although a court order is required in most cases, there are concerns that permission will be granted too easily due to limits on judicial independence. Furthermore, surveillance techniques are most often deployed in Indonesia for combatting terrorism, but there is inadequate oversight or checks and balances in place to prevent abuse by those who are conducting the monitoring. The only other law that explicitly states the need for judicial oversight is the Law on Narcotics, but the requisite procedures for that oversight remain unclear

Areas for Further Research

Surveillance is an unavoidable characteristic of cyberspace. The use of sophisticated data mining and analytical tools that collect, mine, and isolate network traffic has spread quickly. Likewise, the market for enhanced surveillance products and services has become a major and growing commercial segment.

Our research on Indonesia is not uncharacteristic of what we’ve seen in other countries today: the government faces urgent public policy issues around cybercrime, national security issues involving insurgencies, regional tensions, and omnipresent concerns about acts of terror. Not surprisingly, we would expect the government to develop or acquire advanced signals intelligence, computer network exploitation, and surveillance capabilities. At the same time, because of many technological systems’ “dual-use” nature, we should not be surprised to find evidence of such technologies making their way into ISPs and telecommunication companies, and even the private businesses who use them for increasingly complex challenges of network management.

Key to this discussion will be the question of oversight, accountability, and transparency around surveillance — particularly surveillance involving government intelligence and law enforcement agencies. As findings emerge of products that can be used or repurposed to put civil society and others at risk, it is imperative that research is directed toward clarifying their end uses. Further research is clearly required to this end in Indonesia.

Footnote:

1 Sinta Dewi Rosadi, Privacy International Draft Report, 2013, p.4.